The 2025.6 Silicon Labs SSDK Z-Wave release changes the familiar DEBUGPRINT utility to ZPAL_LOG. A brief mention of the change is in the Important Changes for the Z-Wave 7.24.0 release however I’ll give a more detailed description of what has changed and how to use this new utility. If you’re trying to upgrade a project from an earlier SDK, this “breaking change” will make that effort more difficult as you have to switch any DPRINT statements to the new ZPAL_LOG format.

DEBUGPRINT

First a little history. The DEBUGPRINT utility came from the original early 2000s Zensys code running on the 8051 8-bit CPU. From the initial 100 series thru the 500 series, DEBUGPRINT was the ONLY debug utility we had! Even though this was the 2000s thru most of the 2010s, debugging using PRINTF was obsolete by the late 1980s – but not for Z-Wave. PRINTF would print out a short message and maybe a hex value or two and we would try to divine what was going on from these tiny details. There were no breakpoints, no ability to single step the CPU or watch RAM or registers change as the code was executing. Because sending characters out the UART would block the CPU until the UART was empty, you could only send a few characters and maybe a hex value. Sending more characters out the UART would alter the flow of the program and either mask the bug or break something else or often cause a watchdog reset! UGH. While primitive, it was all we had and we made do. DEBUGPRINT was easy to enable or disable – just #define DEBUGPRINT in the file you needed the print statements and recompile. Typically, only a few print statements were enabled at a time or the UART would spew out too much detail or messages would get mixed together making gibberish of the output.

Debugging Today

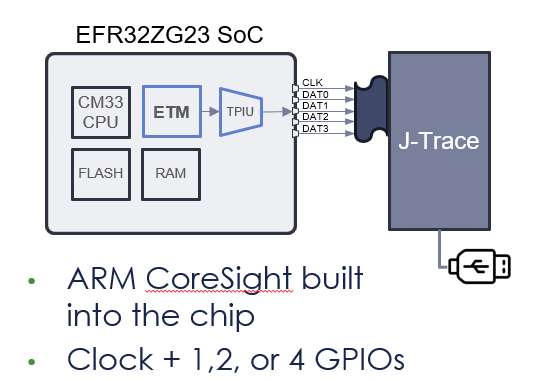

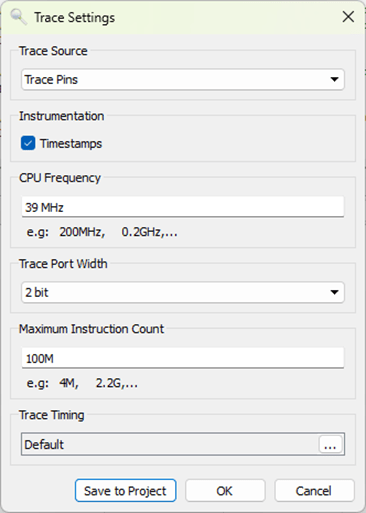

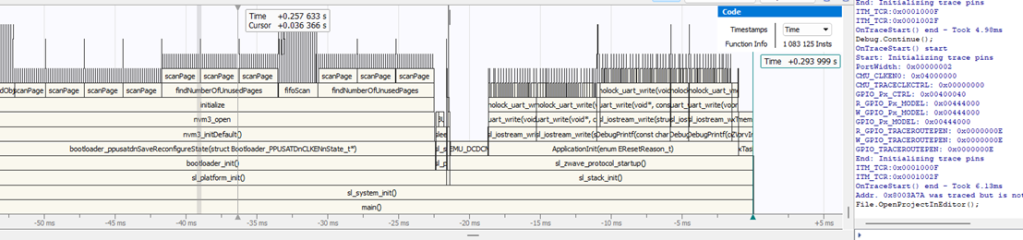

Debug is much easier with the modern ARM CM33 processor on todays Z-Wave chips. We have Single-Wire-Debug (SWD) and can set breakpoints, watchpoints, single step, view memory and peripherals. There’s even Trace where every instruction executed is logged enabling the precise flow of a program to be viewed after the trigger condition of a bug. We still have DEBUGPRINT which is handy for printing out high level messages like “eReset Reason=3′ each time the chip reboots. These messages are handy during debug and were easy to remove prior to building the final production code simply by commenting out the #define.

ZPAL_LOG

The Z-Wave Log component in a Simplicity Studio project .slcp file is installed by default in all the sample applications starting with the 7.24 release. This is good thing and a bad thing. It’s good since it’s already installed and printing messages before you’ve started modifying the code for your project. It’s bad because when you should remove this code for the final production build, we’ll get into that shortly.

General

When you Configure the Z-Wave Log component you get a lot of radio buttons to switch various features on or off. The first block “General” includes:

- Size of the buffer (default is 96 bytes) – Leave this as-is

- Display log level – prints 3 characters identifying Info, Debug, Warnings or Error messages

- Display log source component – prints a number which identifes which module the print statement is from

- Display log timestamp – prints a decimal number of ticks since reset

Enabling any of these messages slightly increases the total FLASH usage. The bigger problem is that it increases the number of characters sent out the UART potentially causing the CPU to block and thus changing the program flow. I recommend leaving these at their defaults.

The Display Log Source component would be useful IF SSv5 decoded the numeric value for you and displayed the name in the console window. Unfortunately it just prints a number which you then must manually decode by looking up the value in the enumerated type zpal_log_component in the zpal_log.h file. The trick would be to send just the numeric number out the UART (thus not taking up significant amounts of time or FLASH) and then SSv5 expanding it to the component name. I have suggested this to the SSv5 team in the past but hasn’t yet come to fruition. The source component is useful if there are several similar or even identical PRINT statements in different blocks of code to help identify where it is coming from. Also if you enable a lot of PRINT statements, it can help narrow down which block a specific message is coming from.

If you enable all 3 of these switches you get: “000000023 [I] (1) ApplicationInit eResetReason = 7”. Where the 00000023 is the timestamp; [i] is the Log Level (Info in this case) and (1) is the component which you have to then decode yourself as mentioned above (ZPAL_LOG_APP in this case) .

Output Channels

The next block is the Output Channels which can enable the four levels of messages: Debug, Info, Warning and Error messages. The default has just Info enabled with the word “vcom” entered into the Info box. I recommend enabling all four of these by entering “vcom” into all four of them. This will increase FLASH usage as the strings for all these messages are now stored on-chip.

Component Filtering

The final configuration block in the Z-Wave Log component is the Component Filtering section. This section has a bunch of radio buttons you can enable which will turn on various messages from the respective module. If you enable ALL of these, it’ll add about 10K bytes of FLASH so maybe only enable ones you think you need.

UART Blocking

The EUSART is only running at 115200 baud which makes each character take over 10 microseconds to send out the UART. This might seem fast, but when you’re transmitting long strings of characters this can seriously impact the program flow in real time. If the UART buffer fills, the code will stall and wait for more buffer space to fill (see the “while” loop in eusart_tx in sl_iostream_eusart.c). If you’re spitting out a lot of messages, the UART will fill causing the program flow to change potentially masking the bug or sending you down the wrong rathole. The baud rate is easily increased to 1mbps which will speed up the printing by 10X which helps, but you need to be aware of the amount of messages pouring out the limited speed of the UART.

Disabling ZPAL_LOG

Once debugging is complete, the next step is to compile all of these messages out of the production code. Fortunately this is easy – just remove “vcom” from all four of the Output Channels section of the Z-Wave Log component. While this removes most of the code for debug messages, the Command Line Interface (CLI) is still there and the EUSART is still used by the sample applications. When developing your own application you will typically want to remove ZPAL_LOG and the CLI as it’s not something your application needs – it is only for the Silicon Labs demos.

Conclusion

Why did silabs make this “breaking change”? I don’t have specific insights from Silicon Labs but the new format provides easily configured “levels” of logging. Is that worth a “breaking change”? I wish they’d spend more time testing the code to reduce the bugs than making a lot of file changes tweaking features that don’t really improve the developers experience. If you’re going to change an important feature, it’s also important to document it which is sorely lacking. But I hope this post helps you utilize this new feature and not be quite so frustrated when updating your project to the latest SDK.